It wasn’t long before the 23 year old lieutenant became commanding officer for an area as large as Denmark. Fifty years later Kjelstrup described his stay as “a relatively quiet and peaceful life in the tropics”. But he had served one of the most brutal regimes in colonial history. Perhaps his photographs, letters and memoirs can help us understand how the young Norwegian felt about being part of this system? >We would like to thank Reidar Kjelstrup and the Kjelstrup family for the kind loan of photographs, documents and objects. Illustrations may not be used without permission from the Kjelstrup family.

Please visit the pages in Norwegian for illustrations and complete text version!

Texts

Adventure, combat and excitement

The Union between Norway and Sweden was dissolved peacefully in 1905, leaving many young officers without a posting in the armed forces. Instead, Lieutenant Kjelstup enlisted for service in the Congo Free State. Kjelstrup hoped that life in the tropics would satisfy his “craving for adventure, combat and excitement.” After a three months training course in Brussels, he set sail for Africa.

To use my abilities

Finn Kjelstrup was soon promoted to military commander of the Haut Kasai Territory, in the south of the country. He ran the remote station of Dilolo, near the border to Portugese West Africa (Angola), and was often the only European at the post. Finn Kjelstrup travelled extensively in the region, recording and mapping. At the station, he set up building projects, began the cultivation of fruit and vegetables and opened a market for soldiers and their families His favourite past time, however, was big game hunting.

A delicate mission

The uniformed soldiers provoked the local people. Many chieftains refused to send carriers to the caravans, deliver food to the soldiers, or to humble themselves in any way. Kjelstrup preferred a diplomatic approach, so that neither side was seen to lose face. He sometimes left his weapons behind when visiting hostile villages, and always returned home safely. Soon after a gift would appear – a hen, some honey, an antelope – a sign that the local chieftain had accepted the colonial representative.

Handsome, kind and devoted

In a letter from 1908, Kjelstrup wrote: ”Blacks are exceeding better than the impression we get of them from accounts and illustrations in Europe. They are handsome, kind and devoted.” Kjelstrup believed it was important to understand the local people’s way of thinking, and studied the book “Études etnographiques” before his meetings with local chieftains. But in keeping with the times, he regarded Africans as less intelligent than Europeans.

Might makes right

At his first military parade in the Congo, the young lieutenant witnessed a soldier being brutally whipped. Kjelstrup vowed that he would deal differently with this type of punishment. Kjelstrup nevertheless admitted that he had been very strict “in the interest of discipline”, something he attributed to his youth and inexperience, and his military education. But to what extent was his actions guided by contemporary European attitudes towards Africans?

The grim reaper

Those who drew to the Congo knew perfectly well that not all would return. Of the 60 Norwegian officers stationed in the Congo, 20 died. Kjelstup established a cemetery for Europeans in Dilolo, and even selected a plot for himself. Kjelstrup made it safely back to Norway, but he had the feeling that he had risen from the dead. He had long resigned himself to a Congolese grave.

Dear Mama

In a letter to his mother from 1908, Finn Kjelstrup apologizes for not writing more often to her. He was then on a two month march to his station in the south of the country. Although dispatches were not regular, he was still able to keep in touch with Norway. His letters tell of exciting encounters with people and wild animals. He also asked his mother to send him a compass and other equipment he lacked. But he told her to keep confidential information about other Norwegians and military matters to herself. In a notebook we find a list of letters he intended to write. One entry reads “Protest to Bruxelles (100 victims)”. What was it Kjelstrup wanted to protest against?

A Sunday picnic

In 1963 Kjeldstup’s son Reidar served in the UN forces in the Congo and was stationed in the same area as his father once had been. There he met Corporal Kabishi of the Congolese military police who remembered learning about his father at school. Many of the details Kabishi remembered tallied with Finn Kjelstrup’s memoirs. The independent Congo of the 1960’s was a very different place than in Lieutenant Finn Kjelstrup’s day. Reidar’s time in the military police was peaceful and he was on good terms with the civil population. He never had to fire his gun.” It was a Sunday picnic compared to what my father experienced”, he comments today.

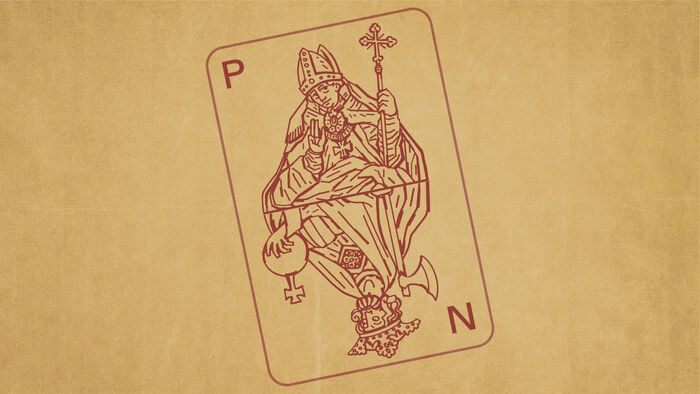

Chair from the Chokwe people

Finn Kjelstrup bestowed 75 objects on the Museum of Cultural Heritage. The most beautiful is the chieftains chair displayed here. It was probably made by the Chokwe people and depicts episodes in the life of a chieftain. It was given to Kjelstrup by the king of the Lunda people, Muata Yamva.